CHAPTER TWO

Cloth Requisites

A bhikkhu has four primary requisites—robe-cloth, food, lodgings, and medicine—and a variety of secondary ones. This and the following five chapters discuss requisites that are allowable and not, along with the proper use of allowable requisites. The suttas provide a background for these discussions by highlighting the proper attitudes that a bhikkhu should develop toward his requisites: He should reflect on their role, not as ends in themselves, but as mere tools toward the training of the mind; and he should develop an attitude of contentment with whatever requisites he receives.

“And what are the effluents to be abandoned by using? There is the case where a bhikkhu, reflecting appropriately, uses robe-cloth simply to counteract cold, to counteract heat, to counteract the touch of flies, mosquitoes, wind, sun, and reptiles; simply for the purpose of covering the parts of the body that cause shame.

“Reflecting appropriately, he uses almsfood, not playfully, nor for intoxication, nor for putting on bulk, nor for beautification; but simply for the survival and continuance of this body, for ending its afflictions, for the support of the holy life, thinking, ‘Thus will I destroy old feelings (of hunger) and not create new feelings (from overeating). I will maintain myself, be blameless, and live in comfort.’

“Reflecting appropriately, he uses lodging simply to counteract cold, to counteract heat, to counteract the touch of flies, mosquitoes, wind, sun, and reptiles; simply for protection from the inclemencies of weather and for the enjoyment of seclusion.

“Reflecting appropriately, he uses medicinal requisites for curing the sick simply to counteract any pains of illness that have arisen and for maximum freedom from disease.

“The effluents, vexation, or fever that would arise if he were not to use these things (in this way) do not arise for him when he uses them (in this way). These are called the effluents to be abandoned by using.”—MN 2

“And how is a bhikkhu content? Just as a bird, wherever it goes, flies with its wings as its only burden, so too is he content with a set of robes to provide for his body and almsfood to provide for his hunger. Wherever he goes, he takes only his barest necessities along. This is how a bhikkhu is content.”—DN 2

“‘This Dhamma is for one who is content, not for one who is discontent.’ Thus was it said. With reference to what was it said? There is the case where a bhikkhu is content with any old robe-cloth at all, any old almsfood, any old lodging, any old medicinal requisites for curing the sick at all. ‘This Dhamma is for one who is content, not for one who is discontent.’ Thus was it said. And with reference to this was it said.”—AN 8:30

Furthermore, for a bhikkhu truly to embody the traditions of the noble ones, he should not only be reflective and content in his use of the requisites, but he should make sure that his reflection and contentment do not lead to pride.

“There is the case where a bhikkhu is content with any old robe-cloth… any old almsfood… any old lodging at all. He does not, for the sake of robe-cloth… almsfood… lodging, do anything unseemly or inappropriate. Not getting robe-cloth… almsfood… lodging, he is not agitated. Getting robe-cloth… almsfood… lodging, he uses it unattached to it, uninfatuated, guiltless, seeing the drawbacks (of attachment to it), and discerning the escape from them. He does not, on account of his contentment with any old robe-cloth… almsfood… lodging at all, exalt himself or disparage others. In this he is diligent, deft, alert, & mindful. This is said to be a bhikkhu standing firm in the ancient, original traditions of the noble ones.”—AN 4:28.

In this way, the requisites fulfill their intended purpose—as aids, rather than obstacles, to the training of the mind.

Robe material

A candidate for ordination must have a set of robes before he can be admitted to the Community as a bhikkhu (Mv.I.70.2). Once ordained he is expected to keep his robes in good repair and to replace them when they get worn beyond use.

The robes may be made from any of six types of robe material: linen, cotton, silk, wool, jute, or hemp (Mv.VIII.2.1). As noted under the discussion of NP 1, the Sub-commentary to that rule includes mixtures of any or all of these types of cloth under “hemp.” There are separate allowances for cloaks, silk cloaks, woolen shawls, and woolen cloth (Mv.VIII.1.36-2.1), but these apparently predated and should be subsumed under the list of six. Nylon, rayon, and other synthetic fabrics are now accepted under the Great Standards.

A bhikkhu may obtain cloth by collecting cast-off cloth, accepting gifts of cloth from householders, or both. The Buddha commended being content with either (Mv.VIII.32).

Robes made from cast-off cloth are one of the four supports, or nissaya, of which a new bhikkhu is informed immediately after ordination. Keeping to this support is one of the thirteen dhutaṅga practices (Thag&16:7). Mv.VIII.4 contains a series of stories concerning groups of bhikkhus who, traveling together, stop and enter a charnel ground to gather cast-off cloth from the corpses there. The resulting rules: If a group goes in together, the members of the group who obtain cloth should give portions to those who don’t. If some of the bhikkhus enter the charnel ground while their fellows stay outside or go in afterward, those who enter (or enter first) don’t have to share any of the cloth they obtain with those who come in afterwards or stay outside and don’t wait for them. However, they must share portions of the cloth they obtain if their fellows do wait or if they have made an agreement beforehand that all are to share in the cloth obtained. The Commentary to Pr 2 discusses the etiquette for taking a piece of cloth from a corpse: Wait until the corpse is cold, to ensure that the spirit of the dead person is no longer in the body.

As for gifts of robe-cloth, Mv.VIII.32 lists eight ways in which a donor may direct his/her gift of cloth:

1. within the territory,

2. within an agreement,

3. where food is prepared,

4. to the Community,

5. to both sides of the Community,

6. to the Community that has spent the Rains,

7. having designated it, and

8. to an individual.

There are complex stipulations governing the ways in which each of these types of gifts is to be handled. Because they are primarily the responsibility of the robe-cloth-distributor, they will be discussed in Chapter 18. However, when bhikkhus are living alone or in small groups without an authorized robe-cloth-distributor, they would be wise to inform themselves of those stipulations, so that they can handle gifts of robe-cloth properly and without offense.

Once a bhikkhu has obtained cloth, he should determine it or place it under shared ownership as discussed under NP 1, NP 3, and Pc 59.

Making Robes: Sewing Instructions

The basic set of robes is three: a double-layer outer robe, a single-layer upper robe, a single-layer lower robe. Up to two of these robes may be made of uncut cloth with a cut border (an anuvāta—see below). Robes without cut borders may not be worn; the same holds true for robes with long borders, floral borders, or snakes’ hood borders. If one obtains a robe without cut borders or with long borders, one may add the missing borders or cut the long borders to an acceptable size and then wear them.

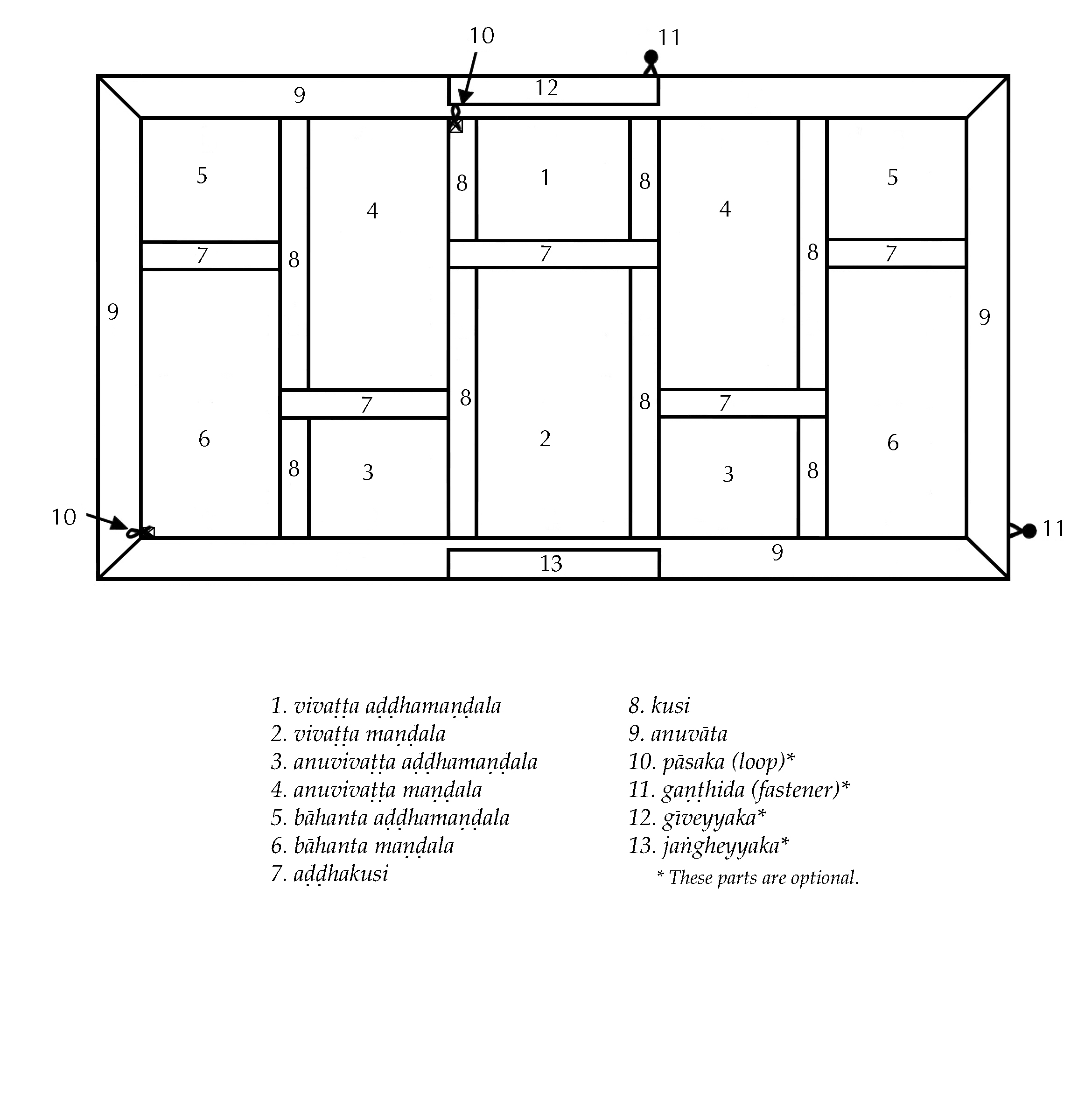

At least one of the robes, however, must be cut. The standard pattern, “like the rice fields of Magadha,” was first devised by Ven. Ānanda at the Buddha’s suggestion. There is no penalty for not following the standard pattern, but keeping to the standard ensures that rag cloth robes will look uniform throughout the Community. It also encourages that large pieces of cloth will get cut, thus reducing the monetary value of any robes made from them and making them less likely to be stolen. See the accompanying diagram.

Each cut robe made to the standard pattern has at least five sections, called khaṇḍas. Although more than five khaṇḍas are allowed, only odd numbers should be used, and not even. The Canon lists names for the parts of the cut robe without explanation. The Commentary interprets them as follows: Each khaṇḍa is composed of a larger piece of cloth, called a maṇḍala (field-plot), and a smaller piece, called an aḍḍhamaṇḍala (half-plot), separated by a small strip, like the dike in a rice field, called an aḍḍhakusi (half-dike). Between each khaṇḍa is a long strip, again like the dike in a rice field, called a kusi (dike). None of the texts mention this point, but it is customary that if the maṇḍala is in the upper part of its khaṇḍa, the maṇḍalas in the neighboring khaṇḍas will be in the lower part of theirs, and vice versa. The central khaṇḍa is called the vivaṭṭa (turning-back); the two khaṇḍas on either side of it, the anuvivaṭṭas; and the remaining khaṇḍas, bāhantas (armpieces), as they wrap around the arms. An alternative interpretation, which the Commentary attributes to the Mahā Aṭṭhakathā, is that all khaṇḍas between the vivaṭṭa and the outermost khaṇḍas are called anuvivaṭṭas, while only the outermost khaṇḍas are called bāhantas. The entire robe is surrounded by a border, called an anuvāta.

Two remaining pieces are mentioned in the Canon, the gīveyyaka (throat-piece) and the jaṅgheyyaka (calf-piece). The Commentary gives two interpretations of these names. The first, which it prefers, is that these are extra layers of cloth, sewn respectively onto the upper robe at the anuvāta wrapping around the neck and onto the lower robe at the anuvāta rubbing against the calves, to protect the robes from the extra wear and tear they tend to get in those places. With the current large size of the upper robe, a jaṅgheyyaka is useful on its lower anuvāta as well. The second interpretation, which for some reason the Vinaya-mukha prefers, is that these pieces are, respectively, the vivaṭṭa and the anuvaṭṭas in the upper robe.

Mv.VIII.12.2 notes that Ven. Ānanda sewed the pieces of cloth together with a rough stitch, so that the robes would be appropriate for contemplatives and not provoke thieves, but this is not a required part of the pattern.

If one needs to make a cut robe but the amount of cloth available is enough only for an uncut robe (i.e., folding the edges of the cut pieces to make a proper seam would use up too much of the cloth), one may use a seam-strip to connect the pieces. This is apparently a long narrow strip of material to which one could stitch the cut pieces without folding them.

Pc 92 sets the maximum size for robes at 6x9 sugata spans. See the discussion under that rule.

A fastener paired with a cloth/thread loop to hold the fasteners may be added to the robe at the neck, and another fastener-loop pair at the lower corners. The fasteners should not be made of fancy materials. Allowable materials are the standard list of ten (mentioned under “Ears” in the preceding chapter) plus thread or cord (tied into a knot). Cloth backings for the fasteners and loops are allowed, to strengthen them. For the fasteners and loops connecting the lower corners of the robe, the cloth backing for the fastener should be put at the edge of the robe, and the cloth backing for the tying loops seven or eight fingerbreadths in from the edge at the other corner.

Repairing Robes

When robes become ragged and worn, one is encouraged to patch them, even—if necessary—to the extent of turning a single-layer robe into a double-layer robe, and the double-layer outer robe into a four-layer one. One is also encouraged to get as much patching material as needed from cast-off cloth and shop-remnant cloth. Mv.VIII.14.2 lists five allowable means of repairing damaged cloth: patching, stitching, folding, sealing (with wax? tree gum?), and strengthening. As often happens with the technical vocabulary of sewing and other skills, there is some doubt about a few of these terms, especially the fourth. The Commentary defines the first as adding a patch after cutting out the old, damaged cloth; and the last as adding a patch without removing the damaged part. Folding would probably cover folding the cloth next to a rip or a frayed edge over the damaged part and then stitching it. Mv.VIII.21.1 lists four additional ways of repairing damaged cloth: a rough stitch, the removing of an uneven edge (according to the Commentary, this refers to cases where one of two pieces at the edge of the robe gets pulled out longer than the other when a thread gets yanked), a border and a binding for the edge of the border (to strengthen a frayed edge), and a network of stitches (the Commentary says that this is a network sewn like the squares on a chess board to help keep two pieces of cloth together; it probably refers to the network of stitches that forms the basis for darning a hole).

Making Robes: Sewing Equipment

One is allowed to cut cloth with a small knife with or without a handle. According to the Commentary, folding knives come under “knife with a handle,” and scissors would probably come here as well. Needles and thimbles may be used in sewing. At present, sewing machines have been accepted under the Great Standards. Knife-handles and thimbles may not be made of fancy materials. Allowable materials are the standard list of ten. To protect these items, one is allowed a piece of felt to wrap the knife and a needle tube for the needles; Pc 60 also indicates that a needle box would be one of a bhikkhu’s standard requisites, although none of the texts explain the difference between the box and the tube. Because Pc 86 forbids needle boxes made of bone, ivory, or horn, both the tube and the box could apparently be made of any of the seven remaining materials in the standard list of ten.

Cv.V.11.2 reports that various substances were used without success to keep needles from rusting—filling the needle tube with yeast, with dried meal, with powdered stone—and the bhikkhus finally settled on powdered stone pounded with beeswax. The Commentary reports that dried meal mixed with turmeric is also an effective rust deterrent. To keep the powdered stone mixture from cracking, one may encase it in a cloth smeared with beeswax. The Commentary reports that the Kurundī includes any cloth-case under “cloth smeared with beeswax,” while the Commentary itself also includes knife-sheaths under this allowance.

To keep these items from getting lost, one is allowed small containers for storing them. To keep the containers orderly, one is allowed a bag for thimbles, with a cord for tying the mouth of the bag that, when the mouth of the bag is closed, can be used as a carrying strap.

To keep cloth aligned while sewing it, one is allowed to use a frame, called a kaṭhina, attached with strings for tying down the pieces of cloth to be sewn together. According to the Commentary, these strings are especially useful in sewing a double-layer robe. Apparently, a Community would have a common frame used by all the bhikkhus, as there are many rules covering its proper use and care. It is not to be set up on uneven ground. A grass mat may be placed under it to keep it from getting worn; and if the edges of the frame do wear out, a binding may be wrapped around them to protect them. If the frame is too big for the robe to be made, one may add extra sticks within the frame to make a smaller frame to the right size. There are also allowances for cords to tie the smaller frame to the larger frame, for threads to tie the cloth to the smaller frame, and for slips of wood to be placed between two layers of cloth. One may also fold back the mat to fit the smaller frame. A ruler or other similar measuring device is allowed to help keep the stitches equidistant; and a marking thread—a thread smeared with turmeric, similar to the graphite string used by carpenters, says the Commentary—to help keep them straight.

There is a dukkaṭa for stepping on the frame with unwashed feet, wet feet, or shod feet. This indicates that the frame is meant to be placed horizontally on the ground when in use. The frame is apparently jointed, for when not in use it may be rolled or folded up around a rod, tied with a cord, and hung from a peg in the wall or an elephant-tusk peg. A special hall or pavilion may be built for storing and using the frame. This is discussed in Chapter 7.

Making Robes: Dyeing

Robes of the following colors should not be worn: entirely blue (or green—the Commentary states that this refers to flax-blue, but the color nīla in the Canon covers all shades of blue and green), entirely yellow, entirely blood-red, entirely crimson, entirely black, entirely orange, or entirely beige (according to the Commentary, this last is the “color of withered leaves”). Apparently, pale versions of these colors—gray under “black,” and purple, pink, or magenta under “crimson”—would also be forbidden. As white is a standard color for lay people’s garments, and as a bhikkhu is forbidden from dressing like a lay person, white robes are forbidden as well. The same holds true for robes made from patterned cloth, although the Vinaya-mukha makes allowances for subtle patterns, such as the ripple pattern called “squirrel’s tail” that Thais sometimes weave into their silk. The Commentary states that if one receives cloth of an unallowable color, then if the color can be removed, remove it and dye the cloth the proper color. It is then allowable for use. If the color can’t be removed, use the cloth for another purpose or insert it as a third layer inside a double-layer robe.

The standard color for robes is brown, although this may shade into reddish, yellow-, or orange-brown. In an origin story, bhikkhus dyed their robes with dung and yellow clay, and the robes came out looking wretched. So the Buddha allowed six kinds of dye: root-dye, stem (wood) dye, bark-dye, leaf-dye, flower-dye, fruit-dye. The Commentary notes, however, that these six categories contain a number of dyes that should not be used. Under root dyes, it advises against turmeric because it fades quickly; under bark dyes, Symplocos racemosa and Mucuna pruritis because they are the wrong color; under wood dyes, Rubia munjista and Rottleria tinctora for the same reason; under leaf dyes, Curculigo orchidoidis and indigo for the same reason—although it also recommends that cloth already worn by lay people should be dyed once in Curculigo orchidoidis. Under flower-dyes, it advises against coral tree (Butea frondosa) and safflower because they are too red. Because the purpose of these dye allowances is that the bhikkhus use dyes giving a fast, even color, commercial chemical dyes are now accepted under the Great Standards.

The following dyeing equipment is allowed: a small dye-pot in which to boil the dye, a collar to tie around the pot just under its mouth to prevent it from boiling over, scoops and ladles, and a basin, pot, or trough for dyeing the cloth. Once the cloth has been dyed, it may be dried by spreading it out on grass matting, hung over a pole or a line, or hung from strings tied to its corners.

The following dyeing techniques are recommended. When the dye is being boiled, one may test to see if it’s fully boiled by placing a drop in clear water or on the back of one’s fingernail. If fully boiled, the Commentary notes, the dye will spread slowly. Once the cloth is hung up to dry, one should turn it upside down repeatedly on the line so that the dye does not run all to one side. One should not leave the cloth unattended until the drips have become discontinuous. If the cloth, once dry, feels stiff, one may soak it in water; if harsh or rough, one may beat it with the hand.

Washing Robes

The Commentary to Pr 2 notes that, when washing robes, one should not put perfume, oil, or sealing wax in the water. This, of course, raises the question of scented detergent. Because unscented detergents are often hard to find, a bhikkhu should be allowed to make use of what is available. If the detergent has a strong scent, he should do his best to rinse it out after washing.

Other Cloth Requisites

In addition to one’s basic set of three robes, one is allowed the following cloth requisites: a felt sitting rug (see NP 11-15); a sitting cloth (see Pc 89); a skin-eruption covering cloth (see Pc 90); and a rains-bathing cloth (see Pc 91). The following articles are also allowed and may be made as large as one likes: a sheet; a handkerchief (literally, a cloth for wiping the face/mouth); requisite-cloth; bags for medicine, sandals, thimbles, etc., with a cord for tying the mouth of the bag as a carrying strap; bandages (listed in the Rules section of Chapter 5); and knee straps. The Canon makes no mention of the shoulder cloth (aṁsa) that many bhikkhus wear at present. It would apparently come under the allowance for requisite-cloths (parikkhāra-cola).

According to the Commentary, the color restrictions applying to robes do not apply to sheets, handkerchiefs, or other cloth requisites. However, they do apply at present to shoulder cloths.

There is some disagreement about which cloth items should be included under “requisite-cloth.” The Commentary allows that spare robes be determined as “requisite-cloth,” but these should be made to the standard size and follow the color restrictions for the basic set of three robes. The Vinaya-mukha prefers to limit the category of requisite-cloth to small cloth items such as bags, water strainers, etc. See the discussion of spare robes under NP 1.

The knee strap is a strip of cloth to help keep the body erect while sitting cross-legged. It is worn around the torso and looped around one or both knees. There is a prohibition against using the outer robe in this manner (see the origin story to Sg 6); and even if the strap is of an allowable sort, only an ill bhikkhu may use it while in an inhabited area (see Sk 26). To make knee straps, bhikkhus are allowed a loom, shuttles, strings, tickets, and all accessories for a loom.

Two styles of waistband are allowed: cloth strips and “pig entrails.” According to the Commentary, the cloth strip may be made of an ordinary weave or a fish-bone weave; other weaves, such as those with large open spaces, are not allowed; a “pig-entrails” waistband is like a single-strand rope with one end woven back in the shape of a key-loop (apparently for inserting the other end of the waistband); a single-strand rope without the hole and other round belts are also allowed. The Canon forbids the following types of waistbands: those with many strands, those like a water-snake head, those braided like a tambourine frame, those like chains.

If the border of the waistband wears out, one may braid the border like a tambourine frame or a chain. If the ends wear out, one may sew them back and knot them in a loop. If the loops wear out, one is allowed a belt fastener, which must be made of one of the allowable materials in the standard list of ten. The Commentary to Pr 2 notes that the fastener should not be made in unusual shapes or incised with decorative patterns, letters, or pictures.

Dressing

There are rules concerning garments that may not be worn at any time, as well as rules concerning garments that must be worn when entering an inhabited area.

Forbidden garments

A bhikkhu who wears any of the following garments, which were the uniform of non-Buddhist sectarians in the Buddha’s time, incurs a thullaccaya: a kusa-grass garment, a bark-fiber garment, a garment of bark pieces, a human-hair blanket, a horse tail-hair blanket, owls’ wings, black antelope hide. The prohibition against black antelope hides covers other animal hides as well.

A bhikkhu who adopts nakedness as an observance also incurs a thullaccaya. If he goes naked for other reasons—as when his robes are stolen—the Vibhaṅga to NP 6 states that he incurs a dukkaṭa. Three kinds of covering are said to count as covering one’s nakedness: a cloth-covering, a sauna-covering, and a water-covering. In other words, there is no offense in being uncovered by cloth in a sauna or in the water (as while bathing). Because saunas in the Buddha’s time were also bathing places, the allowance for sauna-covering would extend to include modern bathrooms as well. In other situations, one should wear at least one’s lower robe. Chapter 8 lists the normally allowable activities that are not allowed while one is naked.

To wear any of the following garments incurs a dukkaṭa: a garment made of swallow-wort (Calotropis gigantea) stalks, a garment made of makaci fiber, jackets or corsets, tirīta-tree (Symplocos racemosa) garments, turbans, woolen cloth with the fleece on the outside, and loincloths. The Commentary states that jackets/ corsets and turbans may be taken apart and the remaining cloth used for robes; that tirīta-tree garments can be used as foot wipers; and that woolen cloth with the fleece inside is allowable. As for loincloths, it says that these are not allowed even when one is ill.

One is also not allowed to wear householder’s upper or lower garments. This refers both to garments tailored in styles worn by householders—such as shirts and trousers—as well as folding or wrapping one’s robes around oneself in styles typical of householders in countries where the basic householder’s garments are, like the bhikkhu’s upper and lower robes, simply rectangular pieces of cloth. According to the Commentary, the prohibition against householder’s upper garments also covers white cloth, no matter how it is worn.

Householder’s ways of wearing the lower garment mentioned in the Canon are the “elephant’s trunk” [C: a roll of cloth hanging down from the navel], the “fish’s tail” [C: the upper corners tied in a knot with two “tails” to either side], the four corners hanging down, the “palmyra-leaf fan” arrangement, the “100 pleats” arrangement. According to the Commentary, one or two pleats in the lower robe when worn in the normal way are acceptable.

The Canon does not mention specific householder ways of wearing an upper garment, but the Commentary lists the following:

1) “like a wanderer” with the chest exposed and the robe thrown back over both shoulders

2) as a cape, covering the back and bringing the two corners over the shoulders to the front;

3) “like drinkers” as a scarf, with the robe wrapped around the neck with two ends hanging down in front over the stomach or thrown over the back;

4) “like a palace lady” covering the head and exposing only the area around the eyes;

5) “like wealthy householders” with the robe cut long so that one end can wrap around the whole body;

6) “like plowmen in a hut” with the robe tucked under one armpit and the rest thrown over the body like a blanket;

7) “like brahmans” with the robe worn as a sash around the back, brought around front under the armpits, with the ends thrown over shoulders;

8) “like text-copying bhikkhus” with the right shoulder exposed, and the robe draped over the left shoulder, exposing the left arm.

To wear the robe in any of these ways out of disrespect, in a monastery or out, it says, entails a dukkaṭa. However, if one has a practical reason to wear the robe in any of these ways—say, as a scarf while sweeping the monastery grounds in cool weather, or “like a palace lady” in a dust storm or under blisteringly hot sun—there should be no offense. The wilderness protocol (Chapter 9) indicates that bhikkhus in the Buddha’s time, while going through the wilderness, wore their upper robe and outer robe folded on or over their heads, and that they did not necessarily have their navels or kneecaps covered with the lower robe.

It was also common, when in the wilderness or in a monastery, to spread out the outer robe, folded, as a groundsheet or sitting cloth (see DN 16, SN 16:11). However, the protocols for eating in a meal hall (Chapter 9) state that there is an offense in spreading out the outer robe and sitting on it in an inhabited area. Some Communities (and the Vinaya-mukha) interpret this as a prohibition against sitting on the outer robe in inhabited areas even when wearing it around the body. This not only creates an awkward situation when visiting a lay person’s house but is also a misinterpretation of the rule.

Required garments

Except on certain occasions, a bhikkhu entering an inhabited area must wear his full set of three robes and take along his rains-bathing cloth. The purpose here is to help protect his robes from being stolen: Any robes left behind could easily fall prey to thieves. Valid reasons for not wearing any of the basic set of three robes while entering an inhabited area are: One is ill, there is sign of rain, one is crossing a river, one’s dwelling is protected with a latch, or the kaṭhina has been spread. Valid reasons for not taking along the rains-bathing cloth are: One is ill, one is going outside the “territory,” one is crossing a river, the dwelling is protected with a latch, the rains-bathing cloth is not made or is unfinished. According to the Commentary, ill here means too sick to carry or wear the robe. Sign of rain refers solely to the four months of the rains. (Some Communities disagree with this definition, and interpret sign of rain as when there is actual rain or sign of approaching rain during any time of the year.) None of the commentaries discuss why “going outside the territory” should be a valid reason for not taking along one’s rains-bathing cloth. If territory (or boundary—sīmā) here means a physical territory, such as the territory of a monastery’s grounds, the allowance makes no sense. If, however, it means a temporal territory—i.e., a set period of time—then it makes perfect sense: If one is traveling outside the four and a half months during which one is allowed to determine and use a rains-bathing cloth (see NP 24), one need not take it along.

Strangely, the Commentary goes on to say that, aside from the allowance to go without one’s full set of robes after the kaṭhina has been spread (see NP 2), only one of the allowances here really counts: that the robes are protected by a latch. In the wilderness, it says, even a latch is not enough. One should put the robe in a container and hide it well in a rock crevice or tree hollow. This may be good practical advice, but because the other allowances are in the Canon they still stand.

The proper way to wear one’s robes in an inhabited area is discussed under Sk 1 & 2: Both the upper and lower robes should be wrapped even all around, and one should be well-covered when entering inhabited areas. These rules provide room for a wide variety of ways of wearing the robe. Some of the possibilities are pictured in the Vinaya-mukha. This, though, is another area where the wisest policy is to adhere to the customs of one’s Community.

Finally, one may not enter an inhabited area without wearing a waistband.

Now at that time a certain bhikkhu, not wearing a waistband, entered a village for alms. Along the road, his lower robe fell off. People, seeing this, hooted and hollered. The bhikkhu was abashed.

According to the Sub-commentary, breaking this rule incurs an offense even when done unintentionally.

Rules

Types of Cloth

“I allow a cloak… I allow a silk cloak… I allow a woolen shawl (§).”—Mv.VIII.1.36

“I allow woolen cloth.”—Mv.VIII.2.1

“I allow six kinds of robe-cloth: linen, cotton, silk, wool, jute (§), and hemp (§).”—Mv.VIII.3.1

Obtaining Cloth

“I allow householder robe-cloth. Whoever wants to, may be a rag-robe man. Whoever wants to, may consent to householder robe-cloth. And I commend contentment with whatever is readily available (§).”—Mv.VIII.1.35

“I allow that one who consents to householder robe-cloth may also consent to rag robes. And I commend contentment with both.”—Mv.VIII.3.2

“And there is the case where people give robe-cloth for bhikkhus who have gone outside the (monastery) territory, (saying,), ‘I give this robe-cloth for so-and-so.” I allow that one consent to it, and there is no counting of the time-span as long as it has not come to his hand (see NP 1, 3, & 28).”—Mv.V.13.13

Gathering Rag-robes in Cemeteries

“I allow you, if you don’t want to, not to give a portion to those who do not wait.”—Mv.VIII.4.1

“I allow, (even) if you don’t want to, that a portion be given to those who wait.”—Mv.VIII.4.2

“I allow you, if you don’t want to, not to give a portion to those who go in afterwards.”—Mv.VIII.4.3

“I allow, (even) if you don’t want to, that a portion be given to those who go in together.”—Mv.VIII.4.4

“I allow, when an agreement has been made, that—(even) if you don’t want to—a portion be given to those who go in.”—Mv.VIII.4.5

Determining/Shared Ownership

“I allow that the three robes be determined but not placed under shared ownership; that the rains-bathing cloth be determined for the four months of the rains, and afterwards placed under shared ownership; that the sitting cloth be determined, not placed under shared ownership; that the sheet be determined, not placed under shared ownership; that the skin-eruption cover cloth be determined as long as one is sick, and afterwards placed under shared ownership; that the handkerchief be determined, not placed under shared ownership; that requisite-cloth be determined, not placed under shared ownership.”—Mv.VIII.20.2

“I allow you to place under shared ownership a cloth at least eight fingerbreadths in length, using the sugata-fingerbreadth, and four fingerbreadths in width.”—Mv.VIII.21.1

Extra Robe-cloth

“Extra robe-cloth (a spare robe) should not be kept/worn. Whoever should keep/wear it is to be dealt with in accordance with the rule (NP 1).”—Mv.VIII.13.6

“I allow that extra robe-cloth (a spare robe) be kept/worn for ten days at most.”—Mv.VIII.13.7

“I allow that extra robe-cloth (a spare robe) be placed under shared ownership.”—Mv.VIII.13.8

Making Robes: Sewing Instructions

“I allow three robes: a double-layer outer robe, a single-layer upper robe, a single-layer lower robe.”—Mv.VIII.13.5

“I allow a cut-up outer robe, a cut-up upper robe, a cut-up lower robe.”—Mv.VIII.12.2

“When the cloths are undamaged, or their damage is repaired, I allow a double-layer outer robe, a single-layer upper robe, a single-layer lower robe; when the cloths are weathered [C: ragged from being kept a long time] and worn, a four-layer outer robe, a double-layer upper robe, a double-layer lower robe. An effort may be made, as much as you need, with regard to cast-off cloth and shop-remnant cloth. I allow a patch [C: a patch after cutting out old, damaged cloth], stitching, folding, sealing (§), reinforcing [C: a patch without removing old damaged cloth] (§).”—Mv.VIII.14.2

“I allow that a rough stitch be made… I allow that the uneven edge be removed… I allow a border and a binding (for the edge of the border) be put on… I allow a network (of stitches) be made.”—Mv.VIII.21.1

“One should not wear robes that have not been cut up. Whoever should wear one: an offense of wrong doing.”—Mv.VIII.11.2

“I allow two cut-up robes, one not cut up… I allow two robes not cut up, one cut up… I allow that a seam-strip (§) be added. But a completely uncut-up (set of robes) should not be worn. Whoever should wear it: an offense of wrong doing.”—Mv.VIII.21.2

“I allow a fastener (for the robe), a loop to tie it with”… “One should not use fancy robe fasteners. Whoever should use one: an offense of wrong doing. I allow that they be made of bone, ivory, horn, reed, bamboo, wood, lac (resin), fruit (§) (e.g., coconut shell), copper (metal), conch-shell, or thread”…. “I allow a cloth backing for the fastener, a cloth backing for the tying loop”… “I allow that the cloth backing for the fasteners be put at the edge of the robe; the cloth backing for the tying loops, seven or eight fingerbreadths in from the edge.”—Cv.V.29.3

Making Other Cloth Requisites

“I allow rains-bathing cloths.”—Mv.VIII.15.15

“I allow a sitting cloth for protecting the body, protecting one’s robes, protecting the lodging.”—Mv.VIII.16.1

Is a sitting cloth without a border permissible?

That is not permissible.

Where is it objected to?

In Sāvatthī, in the Sutta Vibhaṅga (Pc 89)

What offense is committed?

A pācittiya involving cutting down.—Cv.XII.2.8

“I allow felt”…. “Felt is neither to be determined nor placed under shared ownership.”—Cv.V.19.1

“One should not be without (separated from) a sitting cloth for four months. Whoever should do so: an offense of wrong doing.”—Cv.V.18

“I allow that a sheet be made as large as one wants.”—Mv.VIII.16.4

“I allow a skin-eruption covering cloth for anyone with rashes, pustules, running sores, or thick scab diseases.”—Mv.VIII.17

“I allow a bandage.”—Mv.VI.14.5

“I allow a handkerchief (cloth for wiping the face/mouth).”—Mv.VIII.18

“I allow requisite-cloth.”—Mv.VIII.20.1

“I allow a bag for medicine.” “I allow a thread for tying the mouth of the bag as a carrying strap (§).” “I allow a bag for sandals.” “I allow a thread for tying the mouth of the bag as a carrying strap.”—Cv.V.12

“I allow a knee strap (§) for one who is ill”…. (How it is to be made:) “I allow a loom, shuttles, strings, tickets, and all accessories for a loom.”—Cv.V.28.2

Making Robes: Sewing Equipment

“I allow a small knife (a blade), a piece of felt (to wrap around it)”… “I allow a small knife with a handle”… “One should not use fancy small-knife-handles (§). Whoever should use one: an offense of wrong doing. I allow that they be made of bone, ivory, horn, reed, bamboo, wood, lac (resin), fruit (e.g., coconut shell), copper (metal), or conch-shell.”—Cv.V.11.1

“I allow a needle”…. “I allow a needle-tube”…. The needles got rusty. “I allow that (the tube) be filled with yeast”…. “I allow that (the tube) be filled with dried meal”…. “I allow powdered stone”…. “I allow that it (the powdered stone) be pounded with beeswax”…. The powdered stone cracked. “I allow a cloth smeared with beeswax for tying up the powdered stone.”—Cv.V.11.2

“I allow a thimble”…. “One should not use fancy thimbles. Whoever should use one: an offense of wrong doing. I allow that they be made of bone, ivory, horn, reed, bamboo, wood, lac (resin), fruit (e.g., coconut shell), copper (metal), or conch-shell.” Needles, small knives, thimbles got lost. “I allow a small container (for storing these things). The small containers got disordered. “I allow a bag for thimbles.” “I allow thread for tying the mouth of the bag as a carrying strap (§).”—Cv.V.11.5

“I allow a kaṭhina frame, cords for the kaṭhina frame, and that a robe be sewn having tied it down at intervals there.” [C: “Kaṭhina frame” includes mats, etc., to be spread on top of the frame. “Cords” = strings used to tie cloth to the frame when sewing a double-layer robe.]…. “A kaṭhina frame should not be set up on an uneven place. Whoever should do so: an offense of wrong doing”…. “I allow a grass mat (to be placed under the kaṭhina frame)”…. The frame got worn. “I allow a binding for the edge (§)”…. The frame was not the right size (§) [C: too big for the robe being made]. “I allow a stick-frame, a ‘splitting’ (§) [C: folding the edges of the mat to a double thickness to put them in line with the smaller frame], a slip of wood [C: for placing between two layers of cloth], and, having tied the tying cords [C: for tying a smaller frame to a larger frame] and tying threads [C: for tying the cloth to the smaller frame], that a robe be sewn”…. The spaces between the threads were unequal… “I allow a ruler (§).” The stitching was crooked… “I allow a marking thread.”—Cv.V.11.3

“A kaṭhina frame is not to be stepped on with unwashed feet. Whoever should do so: an offense of wrong doing. A kaṭhina frame is not to be stepped on with wet feet. Whoever should do so: an offense of wrong doing. A kaṭhina frame is not to be stepped on with sandaled (feet). Whoever should do so: an offense of wrong doing.”—Cv.V.11.4

“I allow a hall for the kaṭhina-frame, a building for the kaṭhina-frame”…. “I allow that it be made high off the ground”…. “I allow three kinds of pilings to be put up: made of brick, made of stone, made of wood”…. “I allow three kinds of staircases: a staircase made of brick, made of stone, made of wood”…. “I allow a stair railing”…. “I allow that, having lashed on (a roof), it be plastered inside and out with plaster—white, black, or ochre (§)—with garland designs, creeper designs, dragon-teeth designs, five-petaled designs (§), a pole for hanging up robe material (or robes), a cord for hanging up robe material (or robes).”—Cv.V.11.6

“I allow that the kaṭhina frame be folded (rolled) up”…. “I allow that the kaṭhina frame be rolled up around a stick”…. “I allow a cord for tying it up”…. “I allow that it be hung from a peg in the wall or an elephant-tusk peg.”—Cv.V.11.7

Making Robes: Dyeing

“I allow six kinds of dye: root-dye, stem (wood) dye, bark-dye, leaf-dye, flower-dye, fruit-dye.”—Mv.VIII.10.1

“I allow a little dye-pot in which to boil the dye… I allow that a collar (§) be tied on to prevent boiling over… I allow that a drop be placed in water or on the back of the fingernail (to test whether the dye is fully boiled or not).”—Mv.VIII.10.2

“I allow a dye-scoop, a ladle with a handle… I allow a dyeing basin, a dyeing pot… I allow a dyeing trough.”—Mv.VIII.10.3

“I allow a grass matting (on which to dry dyed cloth)… I allow a pole for the robe, a cord (clothesline) for the robe… I allow that it (the cloth) be tied at the corners… I allow a thread/string for tying the corners”… The dye dripped to one side. “I allow that it take the dye being turned back and forth, and that one not leave until the drips have become discontinuous (§).”—Mv.VIII.11.1

“I allow that (stiff dyed cloth) be soaked in water… I allow that (harsh dyed cloth) be beaten with the hand.”—Mv.VIII.11.2

Dressing

“Nakedness, a sectarian observance, is not to be followed. Whoever follows it: a grave offense.”—Mv.VIII.28.1

“I allow three kinds of covering (to count as covering for the body): sauna-covering, water-covering, cloth-covering.”—Cv.V.16.2

“A kusa-grass garment… a bark-fiber garment… a garment of bark pieces… a human hair blanket… a horse tail-hair blanket… owls’ wings… black antelope hide, (each of which is) a sectarian uniform, should not be worn. Whoever should wear one: a grave offense.”—Mv.VIII.28.2

“A garment made of swallow-wort stalks… of makaci fibers (§) should not be worn. Whoever should wear one: an offense of wrong doing.”—Mv.VIII.28.3

“Robes that are entirely blue (or green) should not be worn. Robes that are entirely yellow… entirely blood-red… entirely crimson… entirely black… entirely orange… entirely beige (§) should not be worn. Robes with uncut borders… long borders… floral borders… snakes’ hood borders should not be worn. Jackets/corsets, tirīta-tree garments… turbans should not be worn. Whoever should wear one: an offense of wrong doing.”—Mv.VIII.29

“Woolen cloth with the fleece on the outside should not be worn. Whoever should wear it: an offense of wrong doing.”—Cv.V.4

“Householders’ lower garments (ways of wearing lower cloth)—the ‘elephant’s trunk,’ the ‘fish’s tail,’ the four corners hanging down, the palmyra-leaf fan arrangement, the 100 pleats arrangement—are not to be worn. Whoever should wear them: an offense of wrong doing”…. “Householders’ upper garments are not to be worn. Whoever should wear them: an offense of wrong doing.”—Cv.V.29.4

“A loincloth is not to be worn. Whoever should wear one: an offense of wrong doing.”—Cv.V.29.5

“One should not sit with the outer robe tied as a strap to hold up the knees (§). Whoever should do so: an offense of wrong doing”…. “I allow a knee strap (§) for one who is ill.”—Cv.V.28.2

“One should not enter a village with just an upper and lower robe. Whoever does so: an offense of wrong doing.”—Mv.VIII.23.1

“There are these five reasons for putting aside the outer robe… upper robe… lower robe: One is ill, there is sign of rain, one is crossing a river, the dwelling is protected with a latch, or the kaṭhina has been spread. These are the five reasons for putting aside the outer robe… upper robe… lower robe.

“There are these five reasons for putting aside the rains-bathing cloth: One is ill, one is going outside the territory, one is crossing a river, the dwelling is protected with a latch, the rains-bathing cloth is not made or is unfinished. These are the five reasons for putting aside the rains-bathing cloth.”—Mv.VIII.23.3

“A village is not to be entered by one not wearing a waistband. I allow a waistband.”—Cv.V.29.1

“One should not wear fancy waistbands—those with many strands, those like a water-snake head, those braided like tambourine frames, those like chains. Whoever should wear one: an offense of wrong doing. I allow two kinds of waistbands: cloth strips and ‘pig entrails.’…. The border wore out. “I allow (that the border) be braided like a tambourine frame or like a chain”…. The ends wore out. “I allow that they be sewn back and knotted in a loop”…. The loops wore out. “I allow a belt fastener”…. “One should not use fancy belt fasteners. Whoever should use one: an offense of wrong doing. I allow that they be made of bone, ivory, horn, reed, bamboo, wood, lac (resin), fruit (e.g., coconut shell), copper (metal), conch-shell, or thread.”—Cv.V.29.2